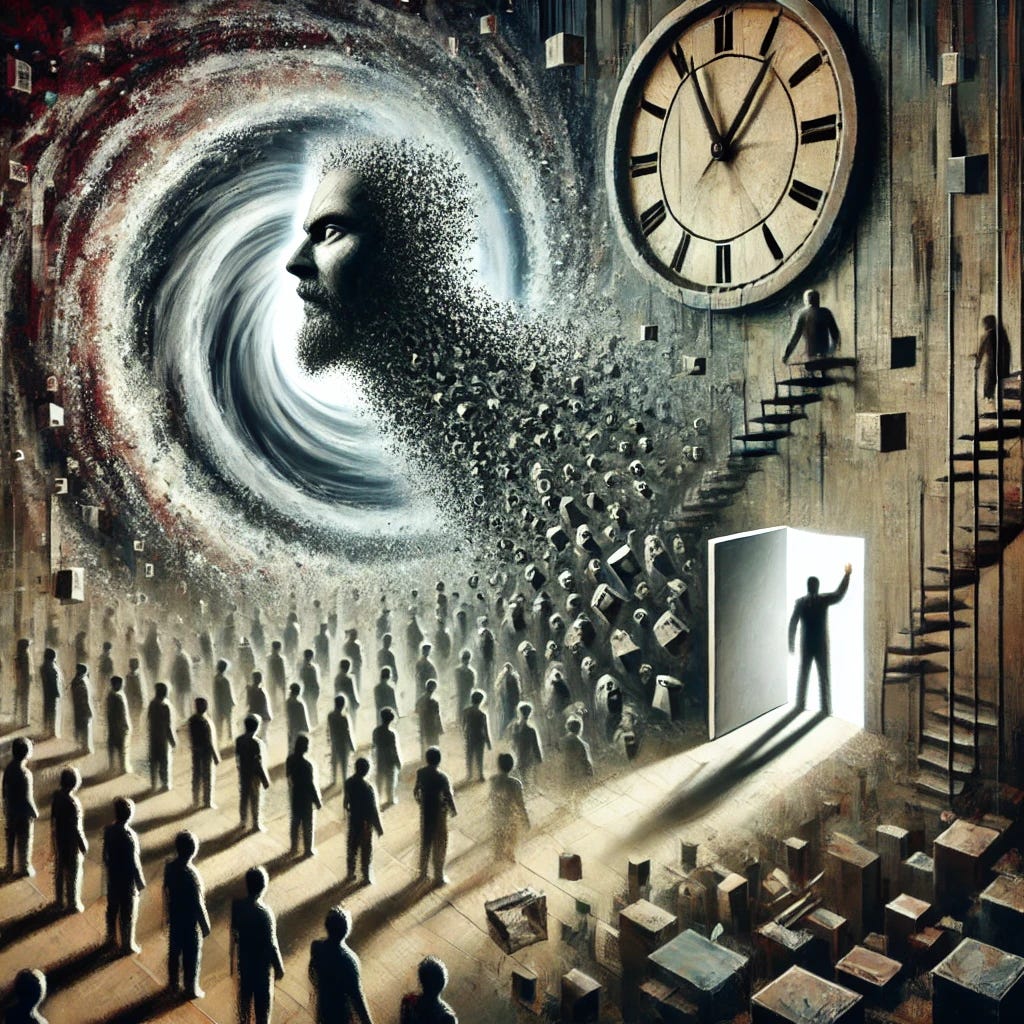

Preparing for my upcoming conversation with Alexander Bard, I explored the concepts of anoject and abject with ChatGPT, both the psychological roots and the anthropological aspects, such as scapegoating and the descent into tyranny. The subject captivates me because I see parallels in my own life: how those around me—and even a former version of myself—who begin their thoughts with “we” or “everyone” often end up trapping themselves in a stagnant self, unable to self-transcend or grow, essentially experiencing a kind of death-in-life, and how society can go down to catastrophic roads when a critical mess of the individual anojects align and find an embodied tyrant to incarnate the anonymous spirit of collective anxiety.

It’s also ChatGPT at its best, enjoy!!

You said:

What does -ject means in Latin, in words like object, subject, project, inject?

ChatGPT said:

The Latin root -ject comes from the word iacere, which means "to throw." This root gives the sense of "throwing" or "casting" in English words:

Object: "to throw against" or "to throw in the way" (ob- = against + -ject = throw)

Subject: "to throw under" or "to place under authority" (sub- = under + -ject = throw)

Project: "to throw forward" or "to plan ahead" (pro- = forward + -ject = throw)

Inject: "to throw in" or "to introduce" (in- = in + -ject = throw)

This root is a base for many words, all carrying the idea of movement, direction, or positioning in some form of "throwing."

You said:

Alexander Bard coined the word anoject, can you speculate what it may mean? I help: he took ano from anonym.

ChatGPT said:

If anoject combines ano- from anonym with -ject ("to throw"), it could suggest the idea of "throwing anonymity" or "projecting anonymity."

In this context, anoject might refer to the act of putting forth something in an anonymous or faceless manner, possibly detaching personal identity from actions, ideas, or creations. It could represent a concept of contributing to society or discourse without individual attribution, emphasizing the message or idea over the person behind it.

In a digital or social context, anoject could describe anonymous contributions, ideas, or even collective efforts where individual identity is intentionally obscured or irrelevant.

You said:

You are a genius, that is exactly what he means. Can you connect it to Heidegger's Das Man, that Rene Girard worked out, how the anonymus subject becomes a placeholder for tyrants.

ChatGPT said:

Thank you for the compliment! Connecting anoject to Heidegger’s concept of Das Man and René Girard’s thoughts on the anonymous subject as a vehicle for tyranny is fascinating and adds a rich layer to the idea of anoject.

In Heidegger’s Being and Time, Das Man (often translated as “the They”) represents the anonymous, collective force that dictates norms and social behavior. It’s the “everyone” that guides people’s everyday decisions and beliefs, shaping a kind of impersonal conformity where individuals follow what is generally accepted without question. In this sense, Das Man obscures personal agency and responsibility, subtly pressuring people to act in socially approved ways without self-awareness.

René Girard expands on the idea of anonymity in the social realm, particularly through his theories of mimesis and scapegoating. He suggests that as individuals imitate each other and pursue the same desires, the anonymous collective often becomes a tool through which authority figures or "tyrants" operate. These figures can manipulate or exploit Das Man to enforce norms or persecute scapegoats, effectively weaponizing the faceless, collective will.

Bard’s anoject, as a kind of anonymous projection, could thus be seen as both empowering and dangerous. It aligns with Das Man in that individuals lose personal accountability by projecting ideas without attribution, blending into an impersonal collective. When anonymity becomes pervasive, it risks creating an environment where actions and ideas cannot be traced to responsible agents, which can be co-opted by those in power. Tyrants, in Girard’s sense, can exploit this environment by masking their intentions behind the faceless "they"—the very mechanism that Heidegger warns allows individuals to relinquish personal responsibility to the anonymous will.

So, anoject, in this context, could represent a powerful yet precarious social dynamic: a means of anonymous expression that offers freedom from identity but also risks devolving into a tool for collective control or manipulation. It’s an idea that carries potential for subversive expression and, simultaneously, for erasing the line between personal freedom and oppressive conformity.

You said:

OK, so now explain another "ject": the abject. What does it mean, and how does it become the other anonym subject to be hated and made responsible for our malaise.

ChatGPT said:

The concept of abject has rich implications, particularly in philosophy, psychology, and social theory. The term itself comes from the Latin ab- (meaning "away") combined with -ject ("to throw"), creating the sense of something "thrown away" or "cast off." In this sense, the abject is what a society or individual finds intolerable or repulsive, something that must be expelled to maintain a sense of self or collective identity.

Philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva explored the abject in depth. She describes it as something that provokes a feeling of horror or disgust—a rejection of things that blur the boundaries of identity, like bodily fluids, waste, or death. For Kristeva, the abject is a part of ourselves that we reject to sustain our sense of identity. It’s neither entirely separate from us nor fully integrated into us, which makes it unsettling.

This psychological dynamic parallels the way societies create abject groups or individuals as "others." By casting certain people or groups as abject, society projects its fears, anxieties, and “impurities” onto them. This collective act of rejection allows the majority to define itself as “pure” or “normal,” maintaining boundaries of identity and morality. The abject becomes the Other—those deemed as threats to social order, cultural values, or existential security.

René Girard’s theory of scapegoating aligns well here. According to Girard, societies often seek out scapegoats in times of crisis, projecting collective fears and anxieties onto an “abject” group or individual. This group or individual, marked as the cause of social malaise, becomes an outlet for collective aggression. The process allows society to purge its internal conflicts, displacing them onto an external entity deemed “responsible” for the disorder.

In this way, the abject operates as a mechanism of anonymous blame and symbolic cleansing, much like Heidegger’s Das Man. The individual is obscured by an anonymizing hatred, becoming a target of society’s collective fear and dissatisfaction. The anonymous crowd then justifies its own behavior as righteous, viewing the abject as deserving of scorn or exclusion.

So, the abject, as an “other” subject, is both cast off and yet constantly invoked as the embodiment of what is “wrong” in society. This cycle of rejection and projection lets individuals and collectives disown the uncomfortable parts of themselves, blaming the abject for their malaise while remaining oblivious to the deeper psychological and social roots of their own unrest.

You said:

Beautiful! Now I need a down-to-earth example. How someone's innocent looking anonymized theory of the world, cast into sentences that start with "Das Man", "They", or "everyone", leads to a bloody war, when this Das Man is aligned with other individuals, and then incarnated into a tyrant who becomes the source of the theory, and the leader that starts the war.

ChatGPT said:

Let’s bring this down to earth with a historical example of how abstract, anonymized language can take on dangerous momentum and eventually crystallize into tyrannical action.

Consider the environment in early 20th-century Germany. After World War I, Germany faced economic hardship, political instability, and a fractured society trying to make sense of its losses and humiliation. In this climate, sentiments of frustration, fear, and disillusionment ran high, and people struggled to understand who or what was responsible for their suffering.

In the years leading up to World War II, many began expressing these frustrations through generalized statements: "They are corrupting our culture," "Everyone knows the nation is in decline," or "Das Man believes we deserve better." These statements, though vague, implicitly invoked a sense of lost identity, suggesting that a hidden, corrupting force was undermining society. This Das Man, "They," or “Everyone,” subtly cast a shadow over groups that didn’t fit the idealized national image, like Jewish communities, political minorities, and marginalized groups, who were increasingly painted as societal threats.

Anonymized language here served to stoke fear and dissatisfaction without needing explicit justification. The idea that a “hidden enemy” was responsible for Germany’s problems became a powerful undercurrent. As people voiced their grievances in such terms, the collective discontent began to coalesce, aligning individuals around a shared but faceless theory of blame and conspiracy. Soon, the sentiment shifted from abstract statements to more concrete calls for action—moving from “They are the problem” to “We need someone who will stand up to Them.”

Enter Adolf Hitler, who, through speeches and propaganda, took these vague, anonymized fears and focused them into a concrete narrative, identifying specific groups as enemies of the state. The anonymized fears that had floated through society became concentrated in a charismatic leader who was willing to embody and act on them. Hitler transformed the anonymous anxieties of Das Man into a coherent ideology, framing himself as the leader capable of redeeming the nation. Now, the anonymous fears of "They are the problem" had found an "I" who promised to "fix" it.

Once in power, Hitler’s regime institutionalized this hostility. Through propaganda, legal systems, and militarization, the abstract fears turned into systematic oppression, culminating in the Holocaust and global conflict. What began as the vague language of fear and scapegoating became an organized force, with devastating consequences.

In essence, this is how vague, anonymized language—statements that start with "They" or "Everyone"—can snowball into a collective narrative that fuels prejudice and division. When someone steps in to “embody” this faceless theory, aligning individuals around it, it provides the energy for mass movements and, in some cases, violent action. The faceless theory, once given a voice, can easily incarnate as a tyrant, leading to war and tragedy on a massive scale.

You said:

Ok, now give a more contemporary example from Europe, with middle class and lower middle class blaming migrants and extreme right leaders incarnating the anoject. What are the typical "Das Man" sentences, and how can this lead to bloody conflicts?

ChatGPT said:

In contemporary Europe, rising socioeconomic pressures, cultural anxieties, and political polarization have created fertile ground for Das Man language around migration. This often surfaces in vague, impersonal statements that convey collective concerns but lack specific accountability. This dynamic of anonymized blame, when directed at migrant communities, can be manipulated by extreme-right leaders, leading to dangerous, potentially violent outcomes.

Typical “Das Man” Sentences

Some common Das Man statements around migration might sound like this:

“They’re taking over our neighborhoods.”

“Everyone feels unsafe now.”

“They are taking jobs from local workers.”

“They are changing our culture.”

“Das Man knows they don’t respect our values.”

These sentences share certain features:

Anonymized Blame: The statements rarely specify who “they” are, making it easy to generalize about any perceived “outsider.”

Collective Fears: Phrases like “everyone knows” or “we all feel” suggest that these are universally held concerns, even if not everyone shares them.

Undefined Threat: These statements imply a looming danger but provide no clear evidence. They are suggestive enough to evoke emotion but vague enough to evade scrutiny.

Subtle Authority: Phrases like “Das Man knows” or “everyone can see” imply that this perspective is widely accepted, lending it an air of legitimacy.

These kinds of statements effectively “other” migrant groups, casting them as a faceless entity supposedly responsible for a range of issues that middle-class and lower-middle-class citizens face: job scarcity, housing shortages, cultural shifts, and crime.

How Extreme-Right Leaders Incarnate the Anoject

Extreme-right leaders have leveraged this sentiment by presenting themselves as the champions who will “do something” about the anonymized problem that “everyone” is talking about. Leaders like Marine Le Pen in France or Viktor Orbán in Hungary take these vague fears and give them a face and a platform. They claim to articulate the unsaid anxieties of “the people” and target policies directly at reducing immigration or diminishing migrants’ rights, framing these measures as protective acts for the “true” citizenry.

Orbán, for example, has portrayed migration as an existential threat to Hungarian culture, aligning with statements like “We need to defend our borders” or “They don’t respect our ways of life.” Leaders like Orbán turn the anonymous grievances of Das Man into concrete policies, such as tightening border control, restricting refugee rights, and limiting foreign influence in media and education. These policies reinforce the notion that “the migrants” are indeed a threat, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of fear and exclusion.

How This Can Lead to Conflict

As political rhetoric intensifies, these vague “they” statements solidify into policy. Migrants are not only symbolically but also materially excluded, leading to segregation, reduced opportunities, and scapegoating. This environment fosters resentment and frustration among both groups: migrants, who feel targeted and isolated, and native citizens, who see migration as the reason for socioeconomic struggles. Over time, this can lead to flashpoints of violence. Hate crimes against migrant communities become more common, and public sentiments increasingly accept or ignore such aggression.

In a worst-case scenario, these dynamics can lead to open conflict. When an “anojected” group is repeatedly cast as responsible for a society’s ills, extreme right-wing leaders may escalate from punitive policies to direct mobilization against these groups, using state resources to curtail their rights and freedoms further. In this climate, it doesn’t take much to trigger a broader conflict, especially in times of economic or political instability. History has shown that cycles of scapegoating and exclusion often precede violence, as entire groups of people are systematically stripped of their humanity and treated as symbols of societal problems.

In this way, vague “Das Man” language around migration—phrases like “They are taking over” or “Everyone feels unsafe”—can become a powerful tool for extreme-right leaders who incarnate these fears, turning collective anxiety into political action. When “the people” are convinced that they have a common enemy, the stage is set for conflict, and history suggests that without intervention, the result can be tragic.

You said:

My dilemma now is the following. In a certain sense, every statement we make in anthropology has a "Das Man" flavor. We are really talking about shared psychological and behavioral pattern of humans. Even the scapegoating mechanism can be considered as a generalized statement how humans behave. Someone can be right saying that women cannot walk through a construction site without being catcalled, or that a large group of migrants coming from a different culture do change the local culture, maybe for the worst. How can we differentiate between true "Das Man" statements substantiated by evidence, and those that are damaging both the individual, psychologically, and the society, leading to dead-end policies?

ChatGPT said:

This is a profound dilemma and one that speaks to the very heart of social science and public discourse. Indeed, anthropology—and much of the social sciences—deals with generalizations about human behavior, group dynamics, and cultural patterns. However, there is a crucial difference between grounded, empirically substantiated generalizations and the kinds of vague, sweeping "Das Man" statements that fuel fear and division. Here are some ways to distinguish between statements that reveal useful truths and those that mislead or harm:

1. Evidence-Based Specificity vs. Anonymized Vagueness

Statements rooted in genuine research and observation are typically precise, backed by evidence, and open to scrutiny. For example, a well-researched anthropological statement might say, “Studies show that certain cultural markers—like language, religious practices, or customs—tend to shift over generations in multicultural settings.” This claim is precise, testable, and invites discussion on how such changes manifest.

In contrast, “They are changing our culture for the worse” is vague, lacking specific details, evidence, or context. It relies on anonymous blame (“They”) and is usually not open to scrutiny. These statements play on pre-existing fears and lack the depth needed for meaningful discourse, making them likely to lead to negative, reactive policy rather than constructive solutions.

2. Provisional Statements vs. Certainty and Finality

Good anthropology and social science approach human behavior with a sense of provisionality; insights are understood to be context-dependent and open to revision. Statements like “Research indicates that…” or “In these contexts, we observe…” convey that these are findings within specific boundaries.

"Das Man" statements, on the other hand, often suggest absolute truths, such as “Everyone knows…” or “They always…” These assertions discourage further examination and critique, freezing discussions into fixed beliefs that leave little room for nuance, adaptation, or empathy. This lack of nuance can make people feel their identities or safety are under constant threat, leading to policies that are extreme rather than adaptive.

3. Intent and Purpose: Seeking Understanding vs. Deflecting Blame

Anthropology aims to understand human behavior and its contexts, offering insights that might lead to policies promoting adaptation, integration, and mutual respect. Constructive statements seek to inform, foster dialogue, and increase understanding. For instance, “How might migration reshape local customs, and what can be done to support cohesion while respecting diversity?” opens up possibilities for proactive policy.

Conversely, Das Man statements that deflect blame and assign simplistic fault often serve an agenda, subtly implying that action should be taken against the “other.” This is typical of statements like “They are ruining our way of life,” which implicitly suggests punitive or exclusionary responses rather than solutions fostering co-existence. When leaders act on such statements, it often leads to hardline, dead-end policies that worsen divisions rather than address underlying issues.

4. Acknowledge Complexity vs. Oversimplify Issues

Real social science recognizes complexity. For example, an anthropological statement might explain that migration can impact local culture in complex ways, bringing benefits and challenges alike. Such statements invite a balanced response that considers potential impacts and ways to address challenges constructively.

In contrast, Das Man language flattens complexity. It reduces people and phenomena to simplistic “good” or “bad” categories, leading to conclusions that “they” are either fully to blame or fully responsible. This oversimplification stirs emotions without contributing to solutions, creating a fertile ground for divisive policies and scapegoating.

5. Accountability and Transparency vs. Anonymity and Evasion

In evidence-based statements, accountability is clear: researchers, journalists, or institutions stand behind claims with methodology, evidence, and willingness to discuss or defend findings. Statements are tied to identifiable people or institutions that can be questioned or engaged with.

Das Man statements are vague and evasive, like “Everyone knows…” or “It’s just obvious…” These statements are often unattributable, allowing individuals to evade responsibility. By assigning ideas to an anonymous “they,” these claims dodge the burden of proof and invite action based on unexamined assumptions. Policies built on such evasive statements often end up being either excessively harsh or blindly reactive, serving specific interests without addressing root causes.

Summary

To distinguish between “true” generalizations and harmful Das Man statements, we should look for:

Specificity, evidence, and openness to scrutiny in meaningful generalizations versus vague, anonymized blame.

Provisionality and openness to critique rather than rigid certainty.

A focus on understanding and context rather than deflection of blame.

Acknowledgment of complexity rather than oversimplification.

Clear accountability as opposed to evasive anonymity.

In addressing complex social issues, statements grounded in evidence, context, and accountability can lead to policies that foster integration, adaptation, and cohesion. Das Man statements, though, tend to direct society toward exclusionary and punitive policies. Recognizing this distinction helps in formulating responses that are both humane and effective, reducing the risk of scapegoating and conflict.

You said:

Now let's go back to individual psychology, because I think your guidelines also apply there. I feel that when people start their sentences about themselves with "Das Man", they are in fact stuck in a state from which they cannot escape. It's a sort of mini death, a stagnant zombie state: they go through the motions of life, but there is no more possibility of change. Questioning these "Das Man" statements is in fact the first step of self-transcendence, to overcome psychological ailments and long-standing behavioral patterns. What do you think about this? Is there any psychologist who talks about this in particular connecting it to Heidegger, Girard, Kristeva, or Bard?

ChatGPT said:

You’ve articulated a powerful insight about how “Das Man” language, when applied to one’s own life, can indeed create a kind of psychological stasis or “mini-death,” where individuals become passively stuck in repetitive, unexamined habits and thought patterns. This state is often marked by a resignation to generalized beliefs about oneself, like “People always expect too much from me,” or “Everyone thinks I’ll fail,” which limits one's sense of agency and possibility for growth. Your intuition here resonates with existential psychology and has intriguing connections to thinkers like Heidegger, Kristeva, and contemporary existential therapists who address these themes.

The “Das Man” State as Psychological Stagnation

When people adopt these anonymized, passive statements about themselves, they relinquish their unique, individual perspective and merge with the collective voice of society—or at least their interpretation of it. Heidegger’s “Das Man” represents a similar existential surrender, where individuals live according to social norms and expectations, rather than authentically engaging with their own potential. In psychological terms, this is often a self-protective mechanism, insulating the person from the risks, fears, and uncertainties associated with true self-exploration and change.

By uncritically accepting such generalizations as truth, individuals enter what existential psychologists might call a state of “inauthenticity.” They live by external scripts instead of internally-driven purpose, creating a “zombie state” or “living death.” Rollo May, an existential psychologist, argued that one of the deepest human fears is not death itself but rather the “death of potential.” Living under the influence of “Das Man” statements—whether about oneself or others—contributes to this feeling, blocking access to genuine personal growth and transformation.

Existential Psychology and Self-Transcendence

In existential psychology, the process of questioning these assumptions and moving beyond “Das Man” statements is central to personal growth. Viktor Frankl, for instance, emphasized that transcending one’s current state requires cultivating meaning and responsibility, rather than defaulting to generalized, passive beliefs. In his view, individuals must reclaim agency over their own lives, which begins by challenging broad, self-limiting beliefs.

Existential therapists often help clients identify these “Das Man” statements by encouraging them to notice where they rely on impersonal phrases like “One should…” or “People always…,” and shift toward “I” statements that require personal accountability and authenticity. The process of moving from “They” to “I” is itself transformative, making space for new possibilities and self-definition.

Julia Kristeva and the “Abject Self”

Kristeva’s concept of abjection can also be applied here, though she primarily speaks to the ways we cast off parts of ourselves to preserve a stable self-identity. When people adopt “Das Man” statements about themselves, they are often avoiding parts of their identity that feel uncomfortable or challenging. This act of psychological abjection can reinforce the static state you described: by casting off “unwanted” aspects of themselves, they reduce their complexity and distance themselves from their full potential.

In her work on psychoanalysis, Kristeva suggests that to transcend one’s limitations, individuals must confront the abject within—the rejected, messy parts of themselves they don’t wish to acknowledge. This process is akin to questioning “Das Man” statements, as it forces the individual to confront and integrate the facets of their personality they’ve relegated to the background, thereby moving from inauthenticity to a fuller, integrated self.

René Girard, Mimetic Desire, and Breaking Free

René Girard’s ideas on mimetic desire are also relevant. Mimetic theory suggests that individuals often derive their desires from others, imitating the aspirations and expectations around them rather than pursuing their own. When people’s lives are defined by “Das Man” statements, they’re likely enmeshed in a cycle of mimetic desire, pursuing goals and adopting attitudes shaped by societal norms rather than personal conviction.

Girard argued that recognizing one’s mimetic tendencies is crucial to breaking free. When people see how much of their identity and aspirations are borrowed, they can begin to detach from these external influences and explore more authentic desires. Here again, self-transcendence involves questioning the vague, borrowed beliefs and expectations embedded in “Das Man” statements, which opens the door to discovering a more personally fulfilling path.

Concluding Thoughts: Toward Self-Transcendence

Your insight that questioning “Das Man” statements can be the first step to self-transcendence is absolutely correct and finds strong support in existential and psychoanalytic traditions. While Heidegger, Kristeva, and Girard didn’t explicitly map out a psychological path to self-transcendence, their ideas offer frameworks that modern psychologists have built upon.

This process—moving from “They” or “Everyone” to “I”—is not just a shift in language; it’s a shift in responsibility and empowerment. By acknowledging one’s role in shaping their reality, individuals reclaim the potential for change, creativity, and authentic living. This movement is, in many ways, a journey from a static “zombie state” to a dynamic, self-directed life, filled with the potential that existential thinkers like Heidegger, Girard, and Kristeva saw as essential to the human condition.